A particular geological formation presents a vertical passage between two rock faces, wider than a crack but narrower than a tunnel. Ascending this feature involves specialized techniques where the climber utilizes opposing pressure against the side walls. An example is observing a seasoned climber carefully wedging their body within the rock cleft, using their feet and back to create a stable upward movement.

Navigating such formations efficiently can significantly broaden access to more complex routes and summits. Historically, mastery of these techniques was essential for traversing challenging terrain where other methods were infeasible. Consequently, skill in this area represents a vital component of a well-rounded climber’s repertoire, enhancing safety and expanding possibilities in mountainous environments.

The subsequent sections will delve into the various methods for effectively negotiating these features, essential equipment considerations, safety protocols, and strategies for practicing and improving competence in this demanding aspect of the sport.

Techniques for Vertical Rock Formations

Effective negotiation of vertical rock formations requires meticulous technique and careful planning. The following guidelines are designed to improve proficiency and safety in these challenging environments.

Tip 1: Establish a Secure Base. Before initiating upward movement, ensure solid contact points with both feet and back, creating a stable platform for subsequent maneuvers. Visual inspection of holds is critical before trusting weight to them.

Tip 2: Employ Opposing Force Strategically. The core principle involves applying outward pressure against both walls of the formation. Fine-tune the balance between opposing forces to maximize efficiency and minimize unnecessary exertion.

Tip 3: Optimize Body Positioning. Adapt the body’s orientation to conform to the available space. Experiment with back-stepping, stemming, and knee-locks to find the most energy-efficient position for the route’s characteristics.

Tip 4: Maintain Controlled Movement. Avoid jerky or abrupt actions, which can destabilize the position and increase the risk of slipping. Focus on slow, deliberate shifts in weight distribution to maintain control.

Tip 5: Manage Rope Drag. Employ longer runners or carefully placed intermediate protection to minimize rope drag, which can significantly impede progress and increase fatigue. Pre-planning the route can often help with this.

Tip 6: Conserve Energy. Avoid prolonged periods of static tension. Regularly assess the situation and adjust the approach to minimize unnecessary muscular effort. Rest whenever feasible.

Tip 7: Practice Proper Footwork. Emphasize precise foot placements to maximize grip and stability. Utilize edging techniques and focus on placing feet on solid, well-defined features. This will conserve energy and limit any slippage issues.

Mastering the techniques outlined above increases efficiency, safety, and overall enjoyment when encountering vertical rock formations during climbs. Consistent practice and careful application of these principles will lead to significant improvement.

The following sections will address specific equipment considerations and advanced strategies for optimizing performance in these unique environments.

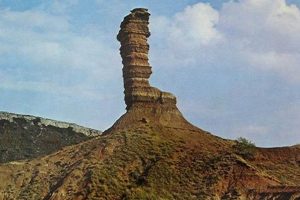

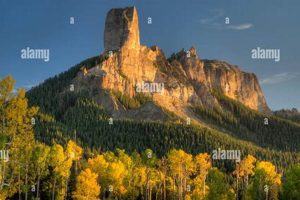

1. Geological Formation

The geological formation is the foundational element determining the existence and characteristics of a rock climbing chimney. Its unique shape and structural integrity dictate the feasibility and technical requirements for ascent.

- Formation Processes

These features are typically created through erosion, tectonic activity, or a combination of both. Differential weathering of softer rock layers surrounded by more resistant strata often leads to their formation. The specific processes involved profoundly influence the dimensions, orientation, and surface texture of the resulting rock cleft.

- Rock Type Composition

The type of rock comprising the geological formation significantly impacts its suitability. Sedimentary rocks, such as sandstone, often provide varied textures suitable for stemming techniques. Conversely, smooth granite may demand advanced friction techniques. The inherent properties of the rock dictate appropriate climbing methods.

- Structural Features and Stability

Joints, fractures, and bedding planes within the rock mass influence stability. A heavily fractured formation presents increased risk due to potential rockfall. Assessment of structural integrity is paramount before commencing an ascent. Competent rock with minimal fracturing offers greater safety margins.

- Dimensional Characteristics

Width, depth, and height are critical dimensional parameters. Wide chimneys may necessitate bridging techniques, while narrower features lend themselves to back-and-footing. The overall length of the feature determines the endurance required for the climb. Dimension analysis informs the selection of suitable techniques and equipment.

Understanding the geological history and composition of a particular rock formation is crucial for evaluating its suitability and selecting appropriate climbing techniques. Careful observation and assessment of these geological features are essential for safe and successful navigation within these formations.

2. Opposing Pressure

Opposing pressure is the fundamental biomechanical principle underlying successful negotiation of a rock climbing chimney. Without consistent, controlled outward force against the opposing walls, upward progress is generally impossible. The physics are straightforward: friction generated by pressing the body against the rock provides the necessary counterforce to gravity. The effectiveness is contingent on the surface texture of the rock, the climber’s body positioning, and the distribution of weight.

The magnitude and direction of force application are critical. Excessive force leads to rapid fatigue, while insufficient pressure results in slippage. Consider a wide chimney where a climber employs a bridging technique; each foot pushes outwards towards the opposite wall, creating a horizontal force vector. This horizontal force, combined with the friction coefficient between the climber’s shoes and the rock surface, generates a vertical force opposing gravity. Precise adjustments in foot placement and body angle are necessary to maintain equilibrium and upward momentum. Furthermore, protection placement must account for the potential for outward pull in the event of a fall.

Mastery of opposing pressure techniques is paramount for safety and efficiency. Proper understanding and execution of these methods permit climbers to ascend challenging formations that would otherwise be impassable. Failure to effectively manage these forces leads to exhaustion, potential injury, or a complete inability to navigate the feature. Thus, a thorough comprehension of the principles of opposing pressure, coupled with deliberate practice, is essential for any climber seeking to advance in this discipline.

3. Chimneying Technique

Chimneying technique represents a specialized skill set directly applicable to the ascent of formations. Proficiency in this area dramatically expands the climber’s capabilities when confronted with such geological features.

- Body Positioning and Balance

Chimneying necessitates maintaining precise body alignment and equilibrium within the confines of the feature. Adjustments in stance, orientation, and center of gravity are critical for efficient movement and energy conservation. An example involves back-stepping, where the climber positions their back against one wall and their feet against the other, using opposing pressure to ascend. Improper positioning leads to instability and increased exertion.

- Footwork and Friction Management

Effective footwork involves utilizing a variety of techniques, including stemming, smearing, and edging, to maximize contact and friction with the rock. Precise placement of feet is essential for generating upward thrust and maintaining stability. Insufficient friction between the climber’s shoes and the rock surface results in slippage and potential falls. A climber needs to continuously assess the surface and adjust their technique accordingly.

- Opposing Force Application

The core principle of chimneying lies in the application of opposing force against the side walls of the formation. This force generates friction, which counteracts gravity and allows the climber to ascend. The distribution of force between the feet and back must be carefully modulated to maintain balance and optimize efficiency. Mismanagement of opposing force leads to either excessive fatigue or inadequate grip.

- Movement Coordination and Rhythm

Successful chimneying involves a coordinated sequence of movements, including shifting weight, adjusting body position, and alternating between pushing and pulling forces. Establishing a consistent rhythm is crucial for maintaining momentum and minimizing wasted energy. Jerky or uncoordinated movements disrupt balance and increase the risk of slipping. Fluidity and predictability are key attributes.

The interconnectedness of these facets underscores the complexity of chimneying technique. Skillful application of these principles significantly enhances safety, efficiency, and overall success when navigating vertical rock formations. Competence in this area is a hallmark of a well-rounded and capable climber, permitting access to challenging routes that would otherwise remain inaccessible.

4. Bridging

Bridging constitutes a fundamental technique employed within formations, particularly those of substantial width. It involves the climber utilizing opposing walls as leverage points, effectively creating a “bridge” with the body to facilitate upward progression.

- Stance and Foot Placement

Bridging requires a wide, stable stance where each foot is placed on opposing walls, often utilizing any available holds or features. The angle of the feet and legs is crucial for generating sufficient outward pressure to maintain balance and prevent slippage. Example: a climber may utilize small protrusions on either wall to elevate the body, simultaneously transferring weight to each foot in alternating movements. The effective use of available footholds contributes to a more secure and efficient bridging maneuver.

- Body Alignment and Weight Distribution

Maintaining proper body alignment is paramount for efficient weight distribution. The climber must position their center of gravity to minimize strain and maximize stability. Overextension or misalignment leads to rapid fatigue and potential loss of contact. An example involves subtly adjusting the angle of the hips and shoulders to counterbalance uneven wall features, promoting a more balanced and sustainable bridging position.

- Dynamic vs. Static Bridging

Bridging can be executed in a static or dynamic manner. Static bridging involves holding a fixed position, conserving energy but limiting upward progress. Dynamic bridging utilizes small, controlled movements to incrementally advance, requiring greater exertion but allowing for sustained ascent. An example is using a series of short “steps” on the walls, alternating weight between feet to move upward, as opposed to remaining in a single, sustained bridging posture.

- Integration with Other Techniques

Bridging is often integrated with other techniques, such as stemming or back-and-footing, to overcome challenging sections. The climber may transition between bridging and other methods to adapt to variations in width and angle within the formation. As an example, the climber uses a stemming technique to pass an obstacle, followed by returning to the bridging position once it is safe.

The mastery of bridging is essential for navigating wider formations, providing a versatile and effective means of upward progression. Proficiency in this technique allows climbers to overcome obstacles and access sections that would otherwise be impassable. It is a testament to the climber’s ability to adapt to the unique challenges presented by varied rock formations. Furthermore, mastering this technique requires thoughtful practice and consistent integration with other techniques.

5. Back-and-Footing

Back-and-footing represents a specialized technique employed in narrow formations, where climbers utilize opposing pressure between their back and feet to ascend. It’s a fundamental skill for navigating these confined spaces, offering a stable and efficient means of upward movement.

- Body Positioning and Opposing Force

The technique requires precise body positioning, typically with the climber’s back against one wall and their feet against the opposite. The outward pressure exerted by the back and feet generates friction, allowing the climber to move upward. For example, a climber might position their back against a textured surface and their feet on small holds across the formation, using the friction to inch upwards. Maintaining consistent pressure is crucial for stability and preventing slippage.

- Footwork and Friction Management

Effective footwork is paramount. Climbers must utilize small holds or irregularities on the rock to maximize contact and generate friction. Techniques like smearing, where the climber presses their feet against the rock surface without specific holds, are often employed. Consider a situation where a climber needs to ascend a smooth section; they may rely solely on smearing to provide sufficient friction for upward movement. Proper footwork minimizes slippage and conserves energy.

- Rhythm and Coordination

Back-and-footing requires a coordinated rhythm between upper and lower body movements. The climber shifts their weight incrementally, alternating pressure between their back and feet to maintain balance and propel themselves upwards. For instance, a climber might first secure their foot placement before adjusting their back position, creating a controlled, rhythmic ascent. Smooth, coordinated movements are more efficient and less fatiguing.

- Energy Conservation and Efficiency

Due to the sustained muscular effort required, energy conservation is crucial. Climbers must strive to optimize their technique to minimize unnecessary exertion. This involves finding efficient body positions, utilizing available holds effectively, and maintaining a consistent pace. One approach is to lean into your back and rest the hands from holding or reaching for holds. An experienced climber will often use small rests or even place gear for aid to conserve energy during the climb.

The integration of these elements – precise body positioning, effective footwork, coordinated rhythm, and energy conservation – defines successful back-and-footing. Mastery of this technique significantly enhances the climber’s ability to navigate narrow rock climbing chimneys, transforming challenging obstacles into surmountable features. Competency in this area is important for safety, efficiency, and the overall climbing experience.

6. Protection Placement

Effective protection placement within rock climbing chimneys is paramount for mitigating the inherent risks associated with this climbing style. The irregular and often constricted nature of these formations presents unique challenges for placing reliable protection and managing rope drag. The following details outline critical considerations for ensuring adequate safety.

- Anchor Selection and Load Distribution

Selection of appropriate anchor points within the chimney is crucial. These points must be capable of withstanding substantial forces in the event of a fall. Natural constrictions, solid rock horns, or well-placed camming devices can serve as anchors. Employing multiple anchor points, when feasible, distributes the load and enhances redundancy. Over-reliance on a single, potentially compromised anchor point creates unacceptable risk.

- Placement Techniques and Gear Considerations

The confined spaces often encountered necessitate specialized placement techniques. Camming devices, due to their ability to expand and grip within parallel cracks, are frequently favored. Placement must be deliberate and secure, ensuring the device is properly seated and engaged. Extenders, or slings, are essential for minimizing rope drag by keeping the rope path as straight as possible. The use of longer runners is often crucial.

- Anticipating Fall Lines and Rope Drag

The unpredictable nature of chimney climbing demands careful anticipation of potential fall lines. Protection should be placed to minimize pendulum swings in the event of a fall. Rope drag can significantly impede progress and increase the force exerted on protection points. Strategic placement of extenders and intermediate protection helps to mitigate these effects. Pre-planning the route, when possible, allows for informed decisions regarding protection placement.

- Rock Quality and Placement Reliability

Assessment of rock quality is paramount before placing protection. Fractured or unstable rock presents an unreliable foundation for anchors. Careful inspection of the rock surface and surrounding area is necessary to identify potential weaknesses. Placement in sound, competent rock is essential for ensuring the protection’s effectiveness. Compromised placements offer a false sense of security and can lead to catastrophic failure.

The integration of these elements underscores the critical role protection placement plays in ensuring climber safety within rock climbing chimneys. A thorough understanding of these principles, coupled with sound judgment and meticulous execution, is essential for mitigating risk and maximizing the likelihood of a successful ascent. Ignoring these considerations can have severe consequences.

7. Rock Type

The geological composition of a rock formation directly influences the characteristics and challenges presented by a rock climbing chimney. Different rock types exhibit varying degrees of friction, structural integrity, and susceptibility to weathering, all of which profoundly impact the climbing experience. For example, a chimney formed in sandstone offers a porous surface with numerous small holds, facilitating stemming and back-and-footing techniques. Conversely, a granite chimney often presents smooth, featureless walls, demanding advanced friction techniques and precise body positioning. The type of rock, therefore, dictates the technical approach and required skillset.

Furthermore, rock type affects the stability and safety of the chimney. Sedimentary rocks like shale are prone to fracturing and weathering, increasing the risk of loose rock and unreliable protection placements. In contrast, igneous rocks like basalt tend to be more solid and durable, providing more secure anchor points. Real-world examples demonstrate this: the frequent rockfall warnings in shale-dominated areas compared to the relative stability of climbs in granite regions. This distinction highlights the critical importance of assessing rock quality before attempting a chimney climb.

In conclusion, rock type is a crucial factor determining the difficulty, required techniques, and overall safety of a rock climbing chimney. Understanding the geological composition of the formation allows climbers to anticipate challenges, select appropriate equipment, and mitigate potential risks. Disregarding the influence of rock type can lead to misjudgment of the climb’s difficulty and increased probability of accidents. Recognizing rock type is a fundamental skill for safe and successful chimney climbing.

Frequently Asked Questions About Rock Climbing Chimneys

The following section addresses common inquiries regarding the unique challenges and techniques associated with rock climbing chimneys.

Question 1: What constitutes a “rock climbing chimney” as distinct from other geological features?

A formation is characterized by a vertical passage between two rock faces, typically wider than a crack climb but narrower than a tunnel. Its defining characteristic is the necessity for specialized techniques, involving opposing pressure against both walls, to facilitate upward progress.

Question 2: What are the primary risks associated with ascending a rock climbing chimney?

Significant risks include rockfall, stemming from loose or unstable rock within the chimney; difficulty in placing adequate protection, due to the constricted space; and increased rope drag, hindering movement and potentially dislodging gear. Careful assessment and mitigation strategies are essential.

Question 3: What specific techniques are most effective for navigating narrow chimneys?

In narrow formations, the back-and-footing technique is commonly employed. This involves using opposing pressure between the back and feet against the sidewalls to ascend. Effective footwork and body positioning are crucial for maximizing friction and maintaining stability.

Question 4: What equipment is considered essential for safe passage of a rock climbing chimney?

Essential equipment includes a variety of camming devices for protection placement, extenders to minimize rope drag, a helmet for protection against rockfall, and appropriate footwear offering good friction. A well-stocked rack and careful gear selection are paramount.

Question 5: How does rock type influence the difficulty and safety of ascending?

Rock type directly affects the friction, stability, and overall challenge. Sandstone offers a more textured surface than granite, while shale is more prone to fracturing than basalt. Understanding the rock’s properties is essential for selecting appropriate techniques and assessing potential hazards.

Question 6: How can climbers effectively conserve energy while ascending a rock climbing chimney?

Energy conservation involves maintaining efficient body positioning, utilizing proper footwork, placing protection strategically to minimize rope drag, and taking advantage of available rests. Avoiding unnecessary exertion and maintaining a steady pace are crucial for prolonged ascents.

Mastery of techniques and equipment usage is essential for a safe and enjoyable ascent.

The following section will address key safety protocols.

Rock Climbing Chimney

This exploration of the rock climbing chimney has illuminated its unique characteristics and challenges. The discussion encompassed geological formation, specialized climbing techniques, protection strategies, and the influence of rock type. Emphasis has been placed on the need for a thorough understanding of opposing pressure mechanics, efficient body positioning, and the importance of sound judgment in mitigating inherent risks.

Proficiency in navigating this particular geological formation requires diligent practice, careful planning, and a commitment to safety. Mastery of the rock climbing chimney significantly expands the climber’s capabilities, opening access to demanding routes and fostering a deeper appreciation for the complexities of the natural environment. Continued study and adherence to established protocols remain paramount for responsible engagement with this challenging aspect of the sport.