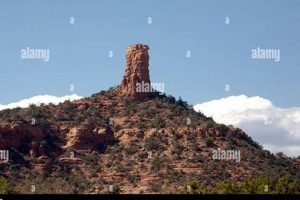

This landform, characterized by its prominent, towering rock formation resembling a vertical flue, frequently stands isolated in a body of water. These geological structures often result from differential erosion, where softer surrounding materials are worn away, leaving a more resistant column. A prime example is a notable geographical feature situated off the coast of a specific region, easily recognizable due to its distinctive shape.

These landmark formations are crucial to the identity and ecology of their respective areas. Their presence often signifies unique geological history and provides habitats for specialized flora and fauna. Historically, such a distinctive feature has served as a navigational aid, a place of cultural significance for indigenous populations, and a source of inspiration for artists and writers. Their preservation is paramount for maintaining regional biodiversity and cultural heritage.

The subsequent sections will delve into the geological processes that create such formations, the ecological impact on the surrounding environment, and the preservation efforts undertaken to protect these natural monuments. We will also explore the cultural and historical significance these landmarks hold for the communities that reside near them.

Guidance for Understanding “Chimney Rock Island”

The following guidance offers insights into maximizing comprehension and appreciation of this distinct geographical feature. Each point provides a specific focus area for study and observation.

Tip 1: Analyze the Geological Formation: Examine the specific type of rock composing the formation. Determine its resistance to erosion compared to the surrounding materials. This provides context for understanding its enduring presence.

Tip 2: Study the Surrounding Ecology: Document the unique plant and animal life that thrives in the immediate vicinity. Identify any species specifically adapted to the microclimate created by the formation’s presence.

Tip 3: Research Historical Records: Investigate historical maps, journals, and local narratives related to the island. This can reveal its significance as a navigational aid, a landmark, or a place of cultural importance.

Tip 4: Investigate Erosion Patterns: Observe the weathering processes currently affecting the formation. Analyze the specific agents of erosion at play (wind, water, ice) and their impact on the rock’s structural integrity.

Tip 5: Explore Conservation Efforts: Research any ongoing or proposed conservation initiatives aimed at preserving the landmark and its surrounding environment. Understand the threats it faces and the strategies being implemented to mitigate them.

Tip 6: Compare with Similar Formations: Research other similar geological structures worldwide. Compare and contrast their formation processes, ecological significance, and cultural value. This broadens understanding of these types of features.

Tip 7: Assess the Impact of Tourism: Evaluate the effects of tourism on the island and its environment. Determine whether tourism is managed sustainably to minimize negative impacts.

By focusing on geological composition, ecological dependencies, historical context, and current conservation efforts, a deeper understanding of this landmark feature can be achieved. Its preservation requires an informed and proactive approach.

The next step involves exploring specific case studies of comparable formations and applying these insights to refine preservation strategies.

1. Geological Formation

The geological formation is the fundamental aspect of any structure. Its inherent properties determine its resilience, appearance, and long-term stability. It dictates how it interacts with environmental forces, such as wind and water, and ultimately shapes its destiny over geological timescales. This is especially true for geographically isolated structures.

- Differential Erosion

Differential erosion is the primary process responsible for the creation of these features. It occurs when varying rock layers exhibit different resistances to weathering and erosion. Softer, less resistant materials are eroded away more quickly, leaving behind the more durable rock in the form of a tall, pillar-like structure. The composition and structure of these rock layers are crucial factors.

- Lithology and Stratigraphy

The lithology, or physical characteristics of the rocks (such as mineral composition, grain size, and cementation), and the stratigraphy, or layering and arrangement of rock strata, directly influence the formation’s susceptibility to erosion. For instance, a cap of harder, erosion-resistant rock (like basalt or sandstone) overlying softer shale or clay provides a protective layer, promoting the formation of the distinctive shape.

- Tectonic Uplift and Sea-Level Changes

Tectonic uplift and fluctuations in sea level play a significant role. Uplift exposes rock formations to increased erosion, while sea-level changes can isolate landforms, turning them into islands. The interaction of these processes shapes the landscape and contributes to the formation’s unique characteristics and geographical context.

- Structural Weaknesses

Pre-existing fractures, faults, and joints within the rock mass act as pathways for water and ice, accelerating the erosional processes. These structural weaknesses can lead to the eventual collapse of portions of the formation, further shaping its appearance and creating new geological features. Understanding these weaknesses is critical for predicting future stability and potential hazards.

The interplay of differential erosion, lithology, stratigraphy, tectonic forces, and structural weaknesses determines the formation’s existence and evolution. Studying these elements provides a comprehensive understanding of the geological history and future trajectory of these significant landforms, and why they often possess such a unique and iconic presence within their environments.

2. Coastal Erosion

Coastal erosion is a critical factor in the formation and ongoing evolution of formations situated near coastlines. This natural process, driven by the relentless action of waves, tides, and currents, directly sculpts these landforms. The differential erosion described previously is amplified in coastal environments, as the constant exposure to marine forces accelerates the wearing away of weaker rock strata. The base of a structure is particularly vulnerable, leading to undercutting and eventual collapse of sections, further refining its unique profile. The intensity of this process varies depending on factors such as wave energy, tidal range, sea level rise, and the geological composition of the coastline. For example, formations along the Pacific coast, exposed to high-energy waves, typically experience more rapid erosion than those in more sheltered locations, such as within bays or estuaries. Understanding these erosional dynamics is crucial for assessing the long-term stability of such landmarks.

The effects of coastal erosion extend beyond the physical alteration of the landscape. It impacts the surrounding ecosystem by altering sediment transport, nutrient availability, and habitat distribution. Eroded material can be deposited elsewhere along the coastline, affecting beach formation and coastal wetlands. Furthermore, increased erosion rates, often exacerbated by human activities such as coastal development and alteration of natural sediment supply, pose a threat to these iconic features. The accelerated loss of land not only diminishes the natural beauty of the coastline but also jeopardizes the ecological integrity of the region. Instances of accelerated erosion around similar coastal landmarks highlight the potential consequences of ignoring these processes. These include the destruction of culturally significant sites and the loss of valuable habitats.

In summary, coastal erosion is an intrinsic component of the lifecycle for formations adjacent to the ocean. Its understanding is paramount for implementing effective conservation strategies. Mitigation efforts might include the construction of sea walls, the replenishment of beach sediment, or the implementation of stricter coastal development regulations. However, any intervention must carefully consider the potential impacts on the surrounding environment and the long-term sustainability of the coastline. Failure to acknowledge and manage coastal erosion effectively will lead to the eventual loss of these natural treasures and the disruption of coastal ecosystems.

3. Habitat Diversity

The presence of these formations significantly influences the diversity of habitats within their immediate vicinity. Their unique geological structures and coastal positioning create varied microclimates and niches, supporting a range of flora and fauna not typically found in the surrounding landscape. This enhanced habitat complexity is critical for regional biodiversity.

- Nesting Sites for Avian Species

The vertical cliffs and isolated nature provide ideal nesting sites for various avian species, including seabirds and raptors. The inaccessibility of the cliffs offers protection from terrestrial predators, while the proximity to marine resources provides a reliable food source. Bird guano also contributes to nutrient enrichment, affecting plant communities.

- Intertidal Zone Ecosystems

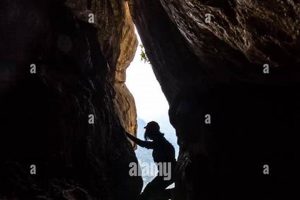

The base of the formation, exposed to tidal fluctuations, supports diverse intertidal ecosystems. These zones provide habitats for a variety of marine invertebrates, such as barnacles, mussels, and sea stars, as well as algae and seaweed. The unique substrate composition of the rock also influences the types of organisms that can thrive in these areas. The degree of tidal exposure, aspect, and wave action each influence the ecosystem.

- Specialized Plant Communities

The sheltered crevices and ledges often support specialized plant communities adapted to the harsh conditions of wind, salt spray, and limited soil. These plants may include drought-resistant succulents, salt-tolerant grasses, and unique lichen species. These plant communities contribute to soil stabilization and provide food and shelter for insects and other small animals.

- Refugia for Marine Mammals

The surrounding waters offer refuge for marine mammals, such as seals and sea lions. The isolated nature provides haul-out sites for resting and breeding, away from human disturbance. The complex underwater topography also creates foraging opportunities and protection from predators. These factors contribute to their ecological value as a critical habitat for coastal wildlife.

The interplay of these factors transforms the formation into a biodiversity hotspot, enriching the ecological landscape. The preservation of these features is essential for maintaining regional biodiversity and supporting the delicate balance of coastal ecosystems. The combined effect of geological structure, marine influence, and isolation creates a range of habitats of considerable importance to the surrounding ecology.

The towering profile of a geological landmark, particularly one situated offshore, inherently serves as a prominent navigational aid. Its unique silhouette, visible from a significant distance at sea, allows mariners to fix their position and maintain course. Prior to the advent of modern satellite-based navigation systems, these features were indispensable for coastal navigation. Their consistent form, enduring over generations, provided a reliable reference point in a featureless ocean landscape. The height, shape, and relative location made them easily identifiable, enabling safe passage through potentially hazardous waters. They functioned as critical visual cues for avoiding reefs, shoals, and treacherous currents.

The historical significance of these geographical landmarks as navigational aids is well-documented. Early explorers, traders, and fishermen relied heavily on their presence. Nautical charts frequently feature detailed depictions of these structures, marking their position and emphasizing their importance for maritime traffic. In many coastal communities, local knowledge regarding these landmarks was passed down through generations of seafarers, representing a crucial aspect of their maritime culture. For instance, certain rock formations off the coast of various regions have been used for centuries, guiding ships into harbors and warning them of dangerous areas. The absence of such easily recognizable landmarks would significantly increase the risk of maritime accidents and impede the efficient flow of maritime commerce.

In conclusion, the role of these distinctive rock islands as navigational landmarks is undeniable. Their natural prominence made them indispensable tools for mariners throughout history. Even in the age of GPS and electronic charts, they retain value as visual confirmation of a vessel’s position and a reminder of the enduring power of natural landmarks in maritime navigation. Understanding their historical significance and practical utility reinforces their importance not only as geological formations but as integral components of maritime history and safety. The preservation of these landmarks is therefore not only a matter of environmental conservation but also a recognition of their lasting contribution to maritime navigation.

5. Cultural Significance

The cultural significance attributed to prominent rock islands often stems from their visual dominance and historical presence within a landscape. These natural formations frequently become imbued with symbolic meaning, serving as focal points for local narratives, traditions, and artistic expressions. Their physical prominence can inspire a sense of awe and reverence, leading to their incorporation into the mythology or spiritual beliefs of indigenous populations. The association between the physical feature and cultural identity solidifies over generations through oral histories, ceremonies, and artistic representations. The presence of such a landmark can act as a unifying element within a community, reinforcing a shared sense of place and collective memory.

One demonstrable example exists within several Pacific Island cultures, where towering rock islands are considered sacred sites, representing ancestral spirits or deities. Access to these areas is often restricted or subject to specific protocols, reflecting the deep respect and spiritual significance they hold. In other instances, these formations are depicted in traditional artwork, songs, and dances, serving as a tangible link to the cultural heritage of the region. Their image may also be incorporated into tribal emblems or flags, symbolizing the unique identity of the community. This association is not limited to pre-industrial societies; even in modern contexts, these landmarks can retain their cultural value, serving as a source of pride and inspiration for local populations. Their continued presence acts as a reminder of the past and a connection to the natural world.

Understanding the cultural significance is paramount for effective conservation and management efforts. Protecting these sites necessitates a holistic approach that considers both their geological integrity and their cultural value. Engaging with local communities and incorporating their perspectives into decision-making processes is crucial for ensuring the long-term preservation of these landmarks. Ignoring the cultural dimension can lead to unintended consequences, alienating local populations and undermining conservation efforts. Recognizing and respecting the cultural significance allows for a more comprehensive and sustainable approach to protecting these natural and cultural treasures, safeguarding them for future generations.

6. Conservation Efforts

The preservation of prominent rock islands demands dedicated conservation efforts due to their inherent vulnerability to environmental degradation and human interference. The geological instability of these formations, exacerbated by coastal erosion and weathering, necessitates measures to mitigate further damage. The unique ecosystems they support, often harboring rare or endemic species, require protection from habitat destruction and invasive species. The cultural significance these sites hold for local communities further underscores the need for responsible stewardship. Conservation initiatives typically encompass a range of strategies, including geological stabilization, habitat restoration, invasive species control, and sustainable tourism management. The specific approach implemented depends on the particular threats facing the specific landmark and the ecological and cultural context in which it exists.

An instance of successful conservation involves a program implemented on an island off the coast of Australia. This program addressed issues of coastal erosion by strategically placing rock armoring at the base, thus helping protect against harsh weather conditions. Invasive species management led to the recovery of nesting bird populations. These are specific, targeted interventions designed to protect both the geological integrity and ecological value of this natural monument. The implementation of visitor management practices has prevented disturbance to sensitive habitats, ensuring that tourism does not compromise conservation goals. Such initiatives highlight the importance of comprehensive planning and adaptive management in protecting the land.

The long-term success of conservation hinges on continued monitoring, research, and community engagement. Changes in environmental conditions, such as sea level rise and increasing storm intensity, require adaptive management strategies to address new challenges. Collaboration between scientists, government agencies, and local stakeholders is essential for developing effective conservation plans and ensuring their sustained implementation. Recognizing the ecological, geological, and cultural value ensures that conservation actions are undertaken with careful consideration to the past, present, and future. Sustaining the heritage for generations to come.

7. Geological Composition

The geological composition is intrinsically linked to the existence and longevity of any such natural landmark. The specific minerals, rock types, and structural arrangements determine its resistance to weathering and erosion. A formation composed of highly resistant rock, such as granite or basalt, will withstand the forces of nature far longer than one composed of softer sedimentary rock like shale or sandstone. The presence of fractures, faults, or bedding planes within the rock mass also significantly influences its stability. For instance, if the uppermost layer consists of a durable caprock overlying less resistant material, the differential erosion process is accelerated, leading to the characteristic “chimney” shape. A real-world example of this can be found in the formations of the American Southwest, where resistant sandstone layers protect underlying shale, creating similar structures. An understanding of geological composition enables predictions of long-term structural behavior and informs appropriate conservation strategies.

The study of geological composition extends to analyzing the rock’s porosity and permeability. Highly porous rock absorbs water, which can freeze and thaw, expanding and contracting to create fractures and accelerate weathering. Permeable rock allows water to seep through, dissolving minerals and weakening the overall structure. The mineral composition also plays a crucial role; certain minerals are more susceptible to chemical weathering, such as oxidation and hydrolysis. This understanding allows for a detailed assessment of the processes affecting its structure and the likely rate of erosion. Detailed geological surveys, including rock sampling and laboratory analysis, are essential tools in evaluating the stability of these landmarks and informing conservation efforts.

In summary, the geological composition is a critical factor in determining the formation, stability, and long-term survival of a structure. Its influence is profound and far-reaching, affecting everything from the shape of the landform to the types of ecological communities it supports. A thorough understanding of the geological composition is essential for effective conservation, requiring ongoing research and monitoring to adapt management strategies to changing environmental conditions. The challenges in this area lie in the complexity of geological processes and the unpredictable nature of environmental forces, requiring a multidisciplinary approach for a lasting preservation of these natural monuments.

Frequently Asked Questions Regarding Chimney Rock Island

This section addresses common inquiries and clarifies prevalent misconceptions surrounding this particular geographical feature. The information provided aims to enhance understanding and promote informed appreciation.

Question 1: What geological processes lead to the formation of Chimney Rock Island?

The formation primarily results from differential erosion. This occurs when varying rock layers exhibit differing resistances to weathering. Softer materials erode faster, leaving behind more resistant rock in a pillar-like structure. Coastal erosion and tectonic uplift also play significant roles.

Question 2: Why are formations often found in coastal regions?

Coastal environments experience intense erosional forces from waves, tides, and currents. This accelerates the differential erosion process. Additionally, tectonic activity and sea-level changes can isolate landmasses, creating island formations.

Question 3: What types of ecological habitats are typically found on and around ?

These areas often support diverse intertidal ecosystems, nesting sites for avian species, specialized plant communities adapted to harsh coastal conditions, and refugia for marine mammals. The unique geology and microclimates foster biodiversity.

Question 4: How significant are the rock islands as navigational landmarks?

Historically, the vertical rocks have served as crucial navigational aids for mariners. Their distinct silhouette allows sailors to fix their position and avoid hazardous areas. Even with modern technology, they remain useful visual references.

Question 5: Do they hold cultural value for local communities?

Yes, these formations frequently possess cultural significance, inspiring mythology, traditions, and artistic expressions. They symbolize cultural heritage, uniting communities and reinforcing a sense of place. They’re commonly portrayed in artwork, ceremonies, and local storytelling.

Question 6: What are the primary threats to their long-term survival, and what conservation efforts are underway?

The primary threats include coastal erosion, geological instability, habitat destruction, and human disturbance. Conservation efforts involve geological stabilization, habitat restoration, invasive species control, and sustainable tourism management. These aim to balance the protection of the structure with the promotion of responsible tourism.

The information presented serves to provide a foundational understanding. Further research into geological processes, ecological systems, and cultural connections will enrich appreciation of these natural wonders.

The following section details the ecological importance and preservation considerations for similar geographical features worldwide.

Chimney Rock Island

The preceding exploration has revealed the complex interplay of geological forces, ecological dependencies, and cultural values inherent to these geographical features. From the differential erosion shaping their dramatic silhouettes to their roles as vital habitats and navigational landmarks, these formations embody a confluence of natural and human history. Understanding the geological composition, mitigating coastal erosion, preserving biodiversity, and respecting cultural significance are paramount for ensuring their continued existence.

The preservation requires an unwavering commitment to conservation, informed by scientific understanding and guided by respect for local communities. The future of these iconic formations depends on proactive stewardship, recognizing their irreplaceable value as both geological wonders and cultural touchstones. Their loss would represent a profound diminishment of our natural and cultural heritage, an outcome to be averted through diligent and sustained effort.