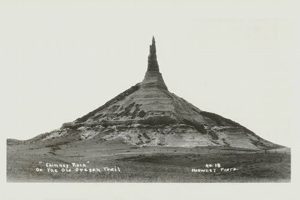

A prominent geological formation in Arizona, this landmark is characterized by its towering, slender shape, resembling a vertical shaft. The structure results from differential erosion, where softer surrounding materials have eroded away, leaving the more resistant column standing. It serves as a striking example of natural sculpting through weathering processes.

These formations hold significant value as visual landmarks, often used for navigation and orientation throughout history. They represent geological time scales and provide insight into past environmental conditions. Furthermore, locations featuring these structures frequently attract tourism, contributing to local economies and promoting appreciation for geological heritage.

The subsequent discussion will elaborate on the specific geological processes contributing to the creation of such formations, their environmental significance, and the management strategies employed to preserve these unique landscapes.

Guidance Regarding Visitation and Preservation

This section provides essential recommendations for those planning to visit, or those interested in the preservation of, sites similar to this notable Arizona landmark. Responsible interaction with such geological formations is crucial for maintaining their integrity and ensuring future generations can appreciate them.

Tip 1: Adhere to Marked Trails: To minimize erosion and protect fragile plant life, confine travel to designated pathways. Straying from these trails can accelerate environmental degradation.

Tip 2: Leave No Trace: Pack out all waste materials. Litter detracts from the natural beauty and can harm local wildlife.

Tip 3: Respect Wildlife: Observe animals from a distance and refrain from feeding them. Human food can disrupt natural feeding patterns and make animals dependent on human sources.

Tip 4: Be Mindful of Fire Hazards: Exercise extreme caution with open flames, especially during dry seasons. Wildfires pose a significant threat to the environment and can cause irreparable damage.

Tip 5: Avoid Climbing or Defacing: Refrain from climbing on the formation or marking it in any way. Such actions can damage the fragile rock and detract from its natural appearance.

Tip 6: Support Conservation Efforts: Consider donating to organizations dedicated to preserving natural landmarks or volunteering in conservation projects. Collective action is essential for long-term protection.

Following these guidelines will ensure a more sustainable and responsible approach to experiencing and safeguarding these important geological treasures. Continued adherence to these practices will allow for their continued appreciation and scientific study.

The subsequent sections will explore the broader implications of geological conservation and the role of tourism in preserving natural wonders.

1. Geological Formation

The geological formation of an Arizona landform directly explains its distinctive morphology. The vertical, pillar-like structure, results from differential erosion acting upon horizontally layered sedimentary rocks. The upper, more resistant caprock protects the underlying, softer strata from rapid weathering. This varying resistance to erosion creates the defining shape. An illustration of this process can be found in similar formations throughout the American Southwest, where sandstone and shale layers exhibit differing erosion rates, leading to the creation of mesas and buttes, analogous in their formative mechanisms. The geological structure is therefore a primary determinant of the landform’s existence and appearance.

The composition of the rock layers, including the mineral content and degree of cementation, plays a pivotal role. For instance, a caprock composed of densely cemented sandstone will provide greater protection than one formed from loosely consolidated material. Fractures and joints within the rock also influence erosion patterns, creating weaknesses that are exploited by water and wind. An appreciation of these geological factors provides a framework for understanding the temporal dimension involved, highlighting the slow, incremental processes that have shaped the landmark over geological timescales. This includes understanding the impact of past climate changes and tectonic activity.

In summary, the geological formation, with its varied rock layers and differential erosion rates, is intrinsically linked to the landmark’s identity. Comprehending these geological characteristics is essential for understanding its formation, predicting its future evolution, and developing effective conservation strategies. The landmark is a tangible expression of geological principles, offering insights into Earth’s dynamic processes.

2. Erosion Processes

Erosion processes are fundamentally responsible for the formation and ongoing modification of geological features, including such landmarks in Arizona. The interplay between various erosional forces shapes the landscape, gradually sculpting the landform into its characteristic form.

- Wind Erosion (Aeolian Processes)

Wind erosion, particularly prevalent in arid environments, contributes to the wearing away of the landmark through abrasion and deflation. Airborne particles, such as sand and silt, act as natural sandblasters, gradually eroding the rock surface. Over extended periods, this process can significantly alter the shape and reduce the mass of the formation. Deflation, the removal of loose surface material by wind, further contributes to the overall erosional process, exposing more rock to weathering.

- Water Erosion (Fluvial Processes)

Although arid regions are defined by limited rainfall, the sporadic but intense precipitation events exert a significant erosional force. Runoff from thunderstorms can carve channels and gullies into the softer layers of sedimentary rock, accelerating the breakdown of the landform. Freeze-thaw cycles, where water penetrates cracks and expands upon freezing, further contribute to the fragmentation of the rock, making it more susceptible to erosion by both wind and water.

- Chemical Weathering

Chemical weathering involves the breakdown of rock through chemical reactions with water, acids, and gases. Oxidation, the reaction of minerals with oxygen, can weaken the rock structure, making it more vulnerable to physical erosion. Carbonation, the dissolution of carbonate minerals by acidic rainwater, can also contribute to the gradual disintegration of the rock. These processes operate on a molecular level, slowly altering the composition and structural integrity of the formation.

- Gravity (Mass Wasting)

Gravity plays a crucial role in erosion through mass wasting processes, such as rockfalls and landslides. As the landform becomes increasingly weathered and eroded, its structural integrity weakens, increasing the likelihood of rockfalls. This process is particularly pronounced on steep slopes, where the force of gravity exerts a greater influence. The accumulation of debris at the base of the formation further contributes to the ongoing cycle of erosion and deposition.

These erosional forces work in concert to shape the geology. The ongoing effects of these processes demonstrate the dynamic nature of geological formations, highlighting the continuous interplay between erosion and resistance. The long-term stability of such geological structures depends on the balance between these forces and the inherent properties of the rock itself.

3. Sedimentary Layers

Sedimentary layers represent a fundamental aspect of geological formations, particularly relevant to understanding the structure and evolution of natural landmarks in Arizona. The distinctive characteristics and arrangement of these layers provide invaluable insights into the geological history and processes that have shaped the region.

- Compositional Variation

Sedimentary layers are composed of various materials, including sand, silt, clay, and gravel, each deposited under different environmental conditions. The composition of a specific layer reflects the source of the sediment and the transportation mechanisms involved. For example, layers composed of well-rounded sand grains suggest deposition in a high-energy environment like a river channel, while finer-grained layers indicate quieter, low-energy conditions such as a lake or floodplain. These variations in composition create distinct visual bands, revealing the history and geological origins. These differences dictate the resistance of each layer to erosion, leading to the sculpted appearance of the formations.

- Stratification and Bedding

Stratification refers to the layering of sedimentary rocks, with each layer representing a distinct depositional event. The thickness and orientation of the beds can provide information about the duration and intensity of the depositional process. Cross-bedding, for example, indicates the migration of sand dunes or ripples, while graded bedding suggests a decrease in flow velocity during deposition. Stratification in geological locations provides a chronological record of environmental changes and the gradual accumulation of sediment. These patterns reveal the direction of past currents and can provide important clues about ancient climates.

- Fossil Content

Sedimentary layers often contain fossils, which are the preserved remains or traces of ancient organisms. Fossils provide direct evidence of past life and can be used to reconstruct ancient ecosystems. The presence of marine fossils in sedimentary layers indicates that the area was once submerged under water. The types of fossils present can also be used to date the rock layers and determine their age. Fossil analysis is a key technique for understanding the geological history of Arizona and for correlating rock layers across different regions.

- Diagenetic Alteration

Diagenesis refers to the physical and chemical changes that occur in sedimentary rocks after deposition. These changes can include compaction, cementation, and recrystallization. Compaction reduces the pore space between sediment grains, while cementation involves the precipitation of minerals that bind the grains together. Recrystallization involves the alteration of existing minerals into new, more stable forms. Diagenetic alteration can significantly affect the strength and permeability of sedimentary rocks, influencing their resistance to erosion. This process can create distinctive weathering patterns, shaping the look and texture. The mineral composition and the degree of alteration can be used to interpret the geological history.

The composition, bedding, fossil content, and diagenetic alteration of sedimentary layers provide a comprehensive understanding of the geological origins and processes shaping these iconic rock formations. By examining the layering, geologists and researchers gain a detailed understanding of the environmental and geological history of the region. Integrating this knowledge with studies of erosion processes and structural geology provides a holistic view of this important landform.

4. Desert Environment

The desert environment plays an integral role in the formation and preservation of geological landmarks, such as those found in Arizona. Arid conditions, characterized by low precipitation and high evaporation rates, exert unique selective pressures on the landscape. These pressures contribute to specific erosional patterns, influence vegetation cover, and shape the overall aesthetic of the region.

- Aridity and Erosion

The scarcity of water in desert environments limits the effectiveness of fluvial erosion. Instead, wind erosion (aeolian processes) and infrequent but intense rainfall events become dominant forces shaping the landscape. Wind-blown sand and dust particles act as abrasive agents, gradually wearing away exposed rock surfaces. Flash floods, though infrequent, can cause significant erosion due to the lack of vegetation cover to intercept the flow of water. These processes contribute to the creation of unique formations by differentially eroding softer rock layers while leaving more resistant strata intact.

- Temperature Fluctuations and Weathering

Extreme temperature fluctuations between day and night in desert environments promote physical weathering. The expansion and contraction of rock due to temperature changes create stresses that lead to fracturing and fragmentation. This process, known as thermal stress weathering, weakens the rock structure and makes it more susceptible to erosion by wind and water. The result is the gradual breakdown of rock formations into smaller fragments, contributing to the formation of talus slopes and desert pavements.

- Sparse Vegetation and Soil Stability

The desert environment’s sparse vegetation cover limits the soil’s ability to resist erosion. The absence of extensive root systems weakens soil structure, making it more vulnerable to wind and water erosion. This lack of vegetation also reduces the amount of organic matter in the soil, further reducing its stability. The fragile desert ecosystem is highly susceptible to disturbance, and even small changes can have significant consequences for soil erosion and the preservation of geological landmarks.

- Desert Varnish and Rock Protection

Desert varnish, a dark coating found on rock surfaces in arid regions, provides a degree of protection against weathering. This coating, composed of clay minerals, iron oxides, and manganese oxides, forms slowly over time through microbial activity and the deposition of atmospheric particles. Desert varnish can help to stabilize rock surfaces and reduce the rate of erosion, contributing to the preservation of these geological formations. The presence and composition of desert varnish also provide valuable clues about past environmental conditions and the history of the rock surface.

The geological landmark is a product of these interacting forces, illustrating the power of the desert environment in shaping landscapes. The aridity, temperature fluctuations, limited vegetation, and desert varnish all contribute to the formation and preservation of these iconic features. Understanding the dynamics of the desert environment is crucial for appreciating the geological evolution and developing appropriate conservation strategies for such landmarks.

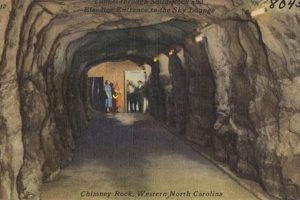

Elevated geological formations, prominently visible across expansive terrains, historically served as crucial navigational aids, particularly before widespread technological solutions existed. The vertical extension and distinct silhouette against the horizon made such structures invaluable reference points for travelers, explorers, and indigenous populations. Specifically, landmarks facilitated directional orientation in regions lacking readily distinguishable topographic features. This reliance on visual markers for navigation directly influenced patterns of exploration, trade routes, and settlement distribution.

The practical application of geological formations as navigational aids is exemplified by various historical accounts and indigenous knowledge systems. Early settlers and explorers often relied on recognizable rock formations to traverse unfamiliar territories, reducing the risk of disorientation and facilitating efficient route planning. Indigenous populations, deeply familiar with their surroundings, integrated the landmark into their oral traditions and maps, using them to define territorial boundaries, locate resources, and transmit knowledge across generations. Evidence of this use is found in historical surveys and records detailing the routes of expeditions and the boundaries established by indigenous communities. This historical utility underscores the integral role played by natural landmarks in human endeavors.

The understanding of geological formations as navigational landmarks provides insight into the human-environment interaction. The identification and utilization of these natural features as navigational aids demonstrate human ingenuity and adaptation to geographic challenges. While modern navigational technology has diminished the reliance on natural landmarks, their historical significance as directional references remains an important aspect of cultural heritage and a testament to the historical relationship between people and their surroundings. Furthermore, recognizing their role underscores the importance of preserving these formations for both their geological value and cultural meaning.

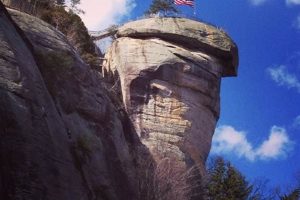

6. Historical Significance

The historical significance of prominent geological formations extends beyond their intrinsic geological value. They often serve as tangible links to past human activities, reflecting cultural narratives, historical events, and societal transformations. The historical resonance embedded within such formations enriches their overall importance and underscores the necessity of their preservation.

- Indigenous Cultural Heritage

Geological features frequently hold deep cultural and spiritual significance for indigenous populations who have inhabited the surrounding regions for centuries. These formations may be associated with creation myths, sacred rituals, and traditional practices. Their presence on ancestral lands connects contemporary indigenous communities to their heritage and reinforces their cultural identity. Preservation efforts should consider the importance of these sites to indigenous cultures, respecting their traditional uses and knowledge.

- Exploration and Settlement Patterns

Distinguishing landmarks often served as vital navigational aids for early explorers and settlers traversing unfamiliar territories. These formations were crucial for mapping routes, establishing settlements, and defining territorial boundaries. Their prominence on historical maps and accounts underscores their role in shaping patterns of exploration and settlement. Understanding their historical context provides insights into the challenges faced by early settlers and the strategies they employed to navigate the landscape.

- Military Campaigns and Strategic Points

In certain instances, geological formations assumed strategic importance during military campaigns and conflicts. Elevated positions provided vantage points for observation and defense, influencing tactical decisions and shaping the outcome of battles. The presence of fortifications or historical markers near these formations serves as a reminder of their role in military history. Analyzing the historical significance within a military context enhances the understanding of past conflicts and their impact on the region.

- Artistic and Literary Inspiration

Distinctive geological formations have frequently served as inspiration for artists, writers, and photographers. Their unique forms and dramatic landscapes have been captured in paintings, photographs, and literary works, contributing to their cultural representation and enhancing their appeal. The artistic depiction in various media has amplified the formation’s recognition and contributed to its allure as a tourist destination.

The historical significance interwoven with a geological landmark provides a rich tapestry of human interaction and cultural narratives. Recognizing and preserving these historical dimensions enriches the understanding and appreciation of natural landscapes. By acknowledging these connections, preservation efforts can ensure the geological formation endures as not only a testament to geological processes, but also as a living legacy of human history and culture.

7. Tourism Attraction

The appeal of geological formations as tourist destinations stems from a confluence of factors, including their visual distinctiveness, accessibility, and association with recreational opportunities. For locations exhibiting unique rock structures, the formations act as primary draws, contributing significantly to regional economies and promoting environmental awareness. Their inherent grandeur and the potential for outdoor activities, such as hiking and photography, solidify their position as favored attractions.

Successful examples of geological feature-based tourism reveal common strategies. Effective marketing campaigns highlight the formations’ unique geological history, promoting educational tourism. Accessible trails and well-maintained visitor facilities enhance the overall experience, encouraging longer stays and repeat visits. Partnerships with local businesses facilitate the creation of tourism packages that incorporate regional cuisine, accommodation, and cultural experiences. Zion National Park, for instance, exemplifies a destination where the geological features are carefully managed to accommodate tourism while safeguarding the environment. Local restaurants in Springdale, Utah, actively cater to park visitors. The economic impact of tourism can be significant, providing employment opportunities and revenue streams for local communities.

Sustaining tourism centered around geological features requires careful management. Uncontrolled access can lead to erosion, vandalism, and habitat degradation, undermining the long-term viability of the attraction. Implementing sustainable tourism practices, such as limiting visitor numbers, establishing designated viewing areas, and promoting responsible behavior, is crucial. Community involvement and education are essential for fostering a sense of stewardship and ensuring the preservation of these formations for future generations. Preserving these natural wonders involves balancing economic benefits with ecological sustainability.

Frequently Asked Questions

The following section addresses common inquiries regarding an Arizona geological landmark, aiming to provide accurate information.

Question 1: What geological processes contributed to the formation of these structures?

Differential erosion, where softer rock layers erode faster than more resistant layers, plays a primary role. Wind and water action, combined with the effects of freeze-thaw cycles, gradually sculpted the formations over millions of years.

Question 2: Are these formations composed of specific rock types?

Typically, these structures consist of sedimentary rocks, such as sandstone, shale, and limestone. The varying composition and hardness of these layers contribute to the distinctive patterns of erosion observed.

Question 3: Is climbing or hiking permitted on the formation?

Restrictions regarding climbing and hiking vary depending on the specific location and management policies. It is essential to consult with local authorities or park services to determine the permitted activities and ensure compliance with safety regulations.

Question 4: How can visitors minimize their impact on the formations?

Visitors can minimize their impact by staying on marked trails, avoiding the removal of rocks or vegetation, and properly disposing of waste. Responsible behavior helps preserve the geological integrity and aesthetic appeal of the formations.

Question 5: Is the formation in a protected area?

The protection status varies depending on the specific location. Some geological sites are located within national parks, monuments, or wilderness areas, while others may be on state or private land. Understanding the protection status is crucial for adhering to relevant regulations and conservation efforts.

Question 6: What are the main threats to the long-term preservation of these formations?

Natural erosion, climate change, and human activities, such as vandalism and uncontrolled tourism, pose the primary threats. Sustainable management practices, conservation efforts, and responsible tourism are essential for mitigating these threats and ensuring long-term preservation.

Understanding these geological formations is crucial for responsible visitation and conservation efforts.

The next section will detail conservation efforts and the importance of geological preservation.

Conclusion

This examination of chimney rock az has highlighted its significance as a geological formation shaped by erosion and its enduring value as a historical landmark. Its sedimentary layers and the surrounding desert environment contribute to its unique characteristics. These natural structures require continued attention to ensure their preservation.

Effective conservation strategies are imperative to protect such geological sites from natural degradation and the impact of human activities. The long-term stewardship of chimney rock az and similar formations relies on collaborative efforts and a commitment to preserving geological heritage for future generations.