A specific rock formation presents a unique challenge in the vertical world. It’s a passage formed by two parallel rock faces, often wider than a crack, where a climber ascends by using opposing pressure between their body and the walls. An example involves navigating a notable geological feature, requiring specialized techniques to overcome the confined space.

The appeal lies in the problem-solving aspect and the full-body engagement required. Historically, these formations provided natural routes through otherwise impassable terrain, serving as crucial pathways for early explorers and climbers. Mastering the necessary skills adds a significant dimension to a climber’s repertoire, enabling access to a broader range of routes and fostering a deeper connection with the rock.

The remainder of this exploration will detail specific techniques for safe and efficient ascents within these formations, examine the required equipment, and highlight prominent locations renowned for their challenging and rewarding features. Further sections will cover the inherent risks and mitigation strategies, ensuring a comprehensive understanding for both novice and experienced practitioners.

Chimney Climbing Techniques and Strategies

Successfully negotiating this type of rock formation demands a nuanced understanding of specific techniques. The following provides essential tips for efficient and safe passage.

Tip 1: Foot Placement is Paramount: Employ a variety of foot placements, including stemming (pressing feet against opposite walls) and bridging (crossing feet) to maintain upward momentum. Minimize reliance on arm strength by optimizing footwork.

Tip 2: Body Positioning for Efficiency: Rotate the body to find the most efficient position for distributing weight and applying pressure. Experiment with back-to-wall, chest-to-wall, and side-to-wall orientations to discover the optimal method for a given section.

Tip 3: Utilize Opposing Forces: Engage opposing muscle groups to generate upward movement. Consciously push with the legs while simultaneously pulling with the arms. Maintain constant pressure against both walls to avoid slippage.

Tip 4: Gear Placement Considerations: Carefully assess the placement of protection. Due to the constricted space, standard placements may be awkward or ineffective. Focus on bomber placements that will hold directional pulls. Consider the potential for pendulum swings in case of a fall.

Tip 5: Conserve Energy: This type of climbing can be physically demanding. Minimize unnecessary movements and maintain a steady, controlled pace. Focus on efficient breathing and relaxation techniques to reduce fatigue.

Tip 6: Manage Rope Drag: The convoluted nature often creates significant rope drag. Extend placements when possible, and consider using longer runners to reduce friction. Communicate clearly with the belayer to minimize rope-related issues.

Tip 7: Back and Shoulder Protection: Continuously scraping on the rock and walls of the route while climbing requires preparation. Thick clothing or pads can minimize any unnecessary damage while working through these tough routes.

Mastery of these techniques promotes efficient and safe ascents, allowing for the confident navigation of vertical challenges. These tips will increase efficiency and minimizes the effort required to ascent on these formations.

The subsequent sections will delve into specific examples of routes, explore the geological formations that create these challenges, and examine the historical significance of this type of climbing.

1. Technique diversity

The ability to employ a wide range of climbing techniques is not merely beneficial, but fundamentally necessary for success. These formations, by their very nature, present varied constrictions, orientations, and surface textures. A climber limited to a narrow set of skills will encounter impassable sections, while a versatile climber can adapt to the changing circumstances. Cause and effect are readily apparent: limited technique leads to failure, while diverse technique facilitates progress. The lack of appropriate technique is one of the largest factors in any failure to summit, or even climb a difficult section.

Consider a hypothetical route featuring a wide, box-like section transitioning into a narrow, overhanging squeeze. The initial section may require stemming or bridging to maintain upward momentum, while the transition demands a change in body position and a reliance on jamming techniques. A climber proficient in stemming but unfamiliar with jamming will struggle significantly at the transition. This example underscores the practical significance of technique diversity; mastery of varied skills translates directly into increased climbing capabilities. Climbing in Yosemite valley, such as the Rostrum, will require the techniques mentioned to move through this formation. In Yosemite, the climbing is difficult and requires constant changes in technique depending on where a climber will be going.

In summary, technique diversity is not merely a desirable attribute; it is a core competency for navigating these formations. The inherent variability of the rock structures necessitates a broad skillset. The ability to adapt to changing conditions determines success or failure. Climbers should focus on expanding their repertoire of techniques to meet the challenges presented, thereby expanding their climbing capabilities. To not do so is to severely limit the difficulty and types of climbs that can be summited and experienced.

2. Body positioning

Optimal body positioning is paramount for efficient and safe navigation of rock formations. Success hinges on effectively distributing weight and leveraging the surrounding rock structure. The narrow confines necessitate strategic adjustments, transforming body placement from a mere preference to a critical determinant of upward progress.

- Spine Orientation and Surface Contact

Spine orientation determines the points of contact with the rock. A back-to-wall position might maximize friction and stability in wider sections. Conversely, a chest-to-wall stance can allow for greater reach and dynamic movement in narrower passages. Variations are essential for adapting to changes in the formation’s dimensions. An effective combination of back contact along with pressing the feet against the rock creates a stable platform for upward movement. The ability to contort and adjust is crucial for navigating varied configurations.

- Weight Distribution and Energy Conservation

Even weight distribution is crucial for conserving energy. Over-reliance on one limb leads to rapid fatigue. The application of opposing forces, pushing with the legs and pulling with the arms, evenly distributes the load. Shifting the center of gravity strategically minimizes stress on individual muscle groups. A climber can maximize endurance through balanced distribution.

- Rotation and Reach Optimization

Body rotation facilitates reach and allows for accessing distant holds. A slight twist can extend the range of motion, enabling a climber to bypass challenging obstacles. Careful rotation improves visibility and provides a better vantage point for assessing the route ahead. By rotating and reaching, difficult holds become accessible.

- Adaptation to Obstacles and Route Trajectory

Body positioning must dynamically adapt to obstacles. Overhangs require a counter-balance strategy, shifting weight away from the protruding section. Variations in the formation’s width demand constant adjustment to maintain equilibrium and momentum. Body positioning becomes a continuous process of adaptation and problem-solving. By modifying stances to match the terrain, climbers overcome challenges.

In summary, body positioning within these formations is not a static posture, but a fluid, adaptive process. Mastery of positional adjustments optimizes efficiency, conserves energy, and enables navigation of complex and challenging rock features. Successful body placement is the key to a successfull ascent.

3. Gear placement

Gear placement within formations necessitates careful consideration due to the unique constraints presented by the confined space. Standard placements may be impractical or ineffective. The placement’s primary function shifts from simply holding a fall to also withstanding directional pulls exerted by the walls. Improper placement increases the risk of gear failure, potentially leading to serious injury. A placement too close to the wall may be levered out during a fall, rendering it useless. The narrowness restricts options, demanding precision and creativity.

The selection of appropriate gear becomes crucial. Cams, with their ability to expand and contract, are often preferred due to their adaptability to varying wall widths. However, careful attention must be paid to rock quality. Soft or crumbling rock may compromise the cam’s holding power. Tricams, specialized devices designed for placements in flared cracks, can also be valuable in these scenarios. The confined space often makes it difficult to visually assess the quality of the placement. The climber must rely on tactile feedback and experience to ensure a secure anchor. A placement near the start of a route provides early safety to the climber.

In summary, gear placement within these formations is a complex and critical skill. The confined space, directional pulls, and varying rock quality demand a high degree of precision and judgment. Selection of appropriate gear and careful assessment of the placement are paramount for safety and success. Mastering these skills mitigates risks and allows climbers to confidently navigate these demanding features. Proper placement is not just about preventing a fall; it is about providing a margin of safety and enabling the climber to focus on the ascent. Climbing within Yosemite is difficult due to rock quality and the wide placements, so the proper gear and placements are absolutely necessary.

4. Rock Geology

The geological composition and formation processes of rock exert a profound influence on the existence and characteristics of rock climbing features. Understanding these geological underpinnings is crucial for predicting the structural integrity, identifying potential hazards, and selecting appropriate climbing techniques and protection strategies.

- Rock Type and Durability

Different rock types, such as granite, sandstone, and limestone, exhibit varying degrees of durability and fracture patterns. Granite, known for its strength and crystalline structure, often forms stable and predictable features. Sandstone, being sedimentary, can be more prone to erosion and feature crumbling holds. Limestone, susceptible to dissolution by water, may contain hidden weaknesses. Climbers must assess the rock type to gauge the reliability of holds and placements. For example, climbing in Yosemite, characterized by its granite formations, demands a different approach than climbing on the sandstone cliffs of Zion National Park.

- Weathering and Erosion

Weathering and erosion processes shape the features over time. Freeze-thaw cycles, chemical weathering, and wind erosion can widen cracks, create loose rock, and alter the texture of the surface. Climbers must recognize the signs of weathering, such as discoloration, scaling, and unstable flakes, to avoid hazardous sections. Areas subjected to heavy rainfall or temperature fluctuations are particularly prone to weathering. Rock texture in these areas can change quickly.

- Structural Features and Fracture Patterns

Joints, faults, and bedding planes represent zones of weakness within the rock mass. These structural features influence the orientation and stability of formations. Climbing routes often follow existing fracture patterns. However, climbers must be aware that these zones may also be prone to collapse. Careful observation of structural features informs route selection and protection placement. For example, a route crossing a prominent fault line may require extra caution due to the increased risk of rockfall.

- Formation Processes and Geological History

The geological history of a region dictates the overall structure and character of the rock formations. Tectonic uplift, volcanic activity, and glacial carving contribute to the creation of the features and determine their overall shape. Understanding the geological history provides valuable insights into the stability and long-term evolution of the climbing area. Areas with a history of seismic activity may be more prone to rockslides or sudden changes in the landscape. Climbers who research the geological history of a location are better prepared to assess the risks and appreciate the unique nature of the climbing experience.

In conclusion, geological factors exert a primary influence on the nature and characteristics of climbing areas. By understanding the rock type, weathering patterns, structural features, and geological history, climbers can better assess the risks, select appropriate techniques, and appreciate the intricate relationship between geology and the climbing experience. Knowledge of the surrounding geology is always recommended before any climbing route.

5. Historical Routes

The historical ascent of these geological formations represents a significant chapter in the development of rock climbing. Early attempts, often undertaken with rudimentary equipment, established routes that continue to challenge climbers today. These routes serve as tangible links to the pioneers of the sport, offering insight into their techniques, strategies, and the prevailing ethos of exploration. The establishment of routes within these formations was instrumental in pushing the boundaries of what was considered possible, inspiring subsequent generations to tackle increasingly difficult challenges. An early ascent represents cause, the effect represents today’s established climbing in the formation.

Examples such as the “Old Route” on the North Face of the Rostrum in Yosemite Valley, a prominent feature, illustrate the evolution of climbing standards and ethics. Early ascents frequently employed aid climbing techniques, utilizing artificial anchors to overcome sections deemed unclimbable by free climbing methods. Over time, many of these routes have been “freed,” meaning that climbers have successfully ascended them using only hands and feet, with ropes and gear serving solely for protection against falls. This shift reflects a growing emphasis on pure climbing skill and a desire to connect with the rock in a more intimate way. The importance to have historical routes represents an understanding of the formation, what is possible, and how to ascend to the top.

Understanding the historical context of routes within these formations is critical for contemporary climbers. It informs route selection, provides valuable beta (information about the climb), and instills a sense of respect for the accomplishments of past climbers. Furthermore, the preservation of these historical routes is essential for maintaining the heritage of rock climbing. Challenges associated with preserving these routes include managing erosion, minimizing the impact of modern climbing practices, and ensuring that future generations have the opportunity to experience these historical challenges. Without the preservation of these historical routes, understanding the past is not possible and hinders climbing abilities.

Frequently Asked Questions

The following addresses common inquiries regarding techniques, safety, and equipment relevant to successful navigation.

Question 1: What constitutes a “feature” in rock climbing terminology?

The term refers to a geological formation characterized by parallel rock faces requiring the use of opposing pressure techniques for ascent. It is often wider than a crack and demands specific climbing skills.

Question 2: Which body positioning techniques provide the most efficiency?

Efficient body positioning involves distributing weight evenly and utilizing opposing forces. Techniques such as back-to-wall, chest-to-wall, and stemming maximize surface contact and minimize energy expenditure.

Question 3: What equipment adaptations are necessary for safe ascents?

Due to the constricted space, specialized gear placement techniques are necessary. Cams and tricams are often preferred due to their adaptability. Careful assessment of rock quality is crucial for ensuring secure placements.

Question 4: How does the composition influence climbing strategy?

Rock type significantly influences the durability and fracture patterns of formations. Granite, sandstone, and limestone each present unique challenges requiring tailored climbing techniques and protection strategies.

Question 5: How important is historical context in climbing this way?

Understanding the historical context of ascents provides valuable insights into the evolution of climbing standards and techniques. Preserving historical routes maintains the heritage of the sport and offers inspiration for contemporary climbers.

Question 6: What are some common mistakes?

Common mistakes include reliance on upper body strength, improper gear placement, and failure to adapt body position to the changing dimensions. Avoiding these errors enhances safety and efficiency.

Efficient climbing requires a combination of the right techniques, body positioning, and gear placement. An understanding of past techniques and a respect for the sport’s past routes is essential to understanding and mastering this technique.

Proceed to the next section for information on specific geographical areas renowned for formations.

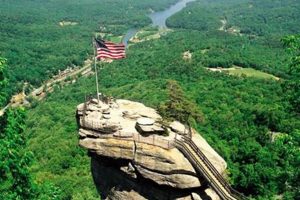

Rock Climbing Chimney Rock

This exploration has detailed essential aspects, encompassing technique diversification, optimized body positioning, and meticulous gear placement. An understanding of geological influences and the historical context of significant routes are essential components for proficient navigation of these unique rock structures. Mastery of these elements contributes to climber safety and successful ascents.

The continued pursuit of knowledge and skill development in rock climbing chimney rock is paramount. Further exploration, coupled with responsible climbing practices, will ensure both personal growth and the preservation of these formations for future generations of climbers. Respect for the rock and a commitment to safe practices will lead to continued exploration in this challenging field.